Vasily Koloda / Unsplash

COVID-19 has caused an extraordinary disruption to children’s education. Young people are having to deal with simultaneous challenges on different time frames. In the short-term COVID-19 has disrupted children’s learning, disproportionately affecting poorer, already vulnerable pupils (see previous articles). In the medium-term this threatens to widen the attainment gap between the richest and the poorest and reduce social mobility. But though schools may only be closed for months, the effects could last a lifetime. In the longer-term there is a risk of entrenched inequality as the poorest young people bear the brunt of multiple challenges from youth unemployment and the changing nature of work to intergenerational inequality, the rising cost of living and climate change. For these reasons I would argue that recovery plans should be youth-centred, putting young people at their heart.

Although COVID-19 has demonstrated the fragility of our world, it has also shown the huge reserves of goodwill and self-sacrifice within our societies and our ability to innovate rapidly. By using this energy we can ‘build back better’ in education and recover from this disaster to make a fairer, greener, more youth-centred world. This article will suggest several steps towards this vision.

Short-term solutions (six months to one year)

The short-term challenge is to get children back in to school and reduce the attainment gap that COVID-19 has exacerbated (see previous articles). In England, on 19th June 2020, the government announced a welcome £1 billion ‘catch-up’ package. This includes £650 million for schools, with commendable freedom for head teachers to spend it as they see fit and a £350 million National Tutoring Programme. The tutoring scheme is exactly the sort of ‘crisis innovation’ that could benefit society long into the future. As Sir Peter Lampl of the Sutton Trust says: ‘The national tutoring programme is a major opportunity to not only reverse the damage done by school closures, but to also build a fairer education system for the future.’

‘the best way to improve English children’s education will be to ensure that they can go back to school’

As well as this package the education system must plan to reopen in September and have contingency plans for an autumn spike in the virus and a new lockdown. Across Europe schools are already open and running shift systems, hygiene rotas, targeted lockdowns in infected areas and teaching training, all of which need to be in place in England before schools can safely reopen. Clearly, the best way to improve English children’s education will be to ensure that they can go back to school.

Across the world developing countries face a huge challenge to get children back into school. UNDP estimates (20th May 2020) that there are now 410 million children out of school without the resources to learn and 30 years of development may be reversed. In recent years middle income countries such as India, where primary school enrolment has been around 96% since 2009, have shifted their focus from children’s access to learning to the quality of that learning. As Dr Rakmini Banerji, CEO of the Indian educational NGO Pratham, said recently (23rd June 2020), countries such as India may have to rewind and ‘relook at enrolment and attendance’.

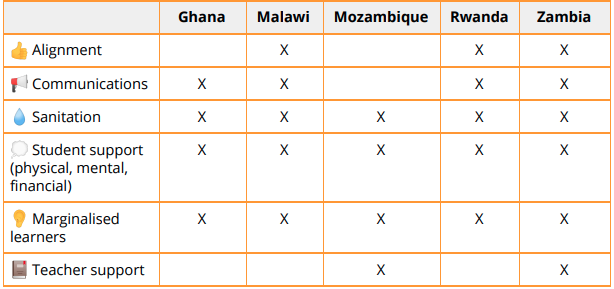

Several countries have developed back-to-school plans and launched campaigns already. The Global Partnership for Education, for example, is funding a 60-day campaign across 16 regions in Ghana and has accelerated $60 million of funding to enable Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia to follow suit. As Table 1 from the EdTech Hub (1st June 2020) shows, these countries, despite having fewer resources, are far ahead of England in preparing detailed plans to support teachers and students, focus on the most marginalized, improve sanitation and build communications and coalitions with schools, parents, NGOs, government and business all aligned to achieve the same goals.

Table 1. Mapping key elements of back-to-school strategies to Global Partnership for Education Funding ($60m). Sources: EdTech Hub / COVID-19 Accelerated Funding Applications from Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia (1st June 2020)

Medium-term solutions (one to two years)

COVID-19 has shown that teachers are the engines of children’s learning. Teachers should be central to any plans to recover lost ground in education. As the Education Endowment Foundation suggests for England, there should be support for teachers to carefully assess which children have fallen behind during COVID-19 and to help them catch up again (for example through tutoring or grouping children by ability rather than by age or grade).

COVID-19 was arguably Edtech’s ‘moment to shine’. But as previous articles in this series have shown, the results are mixed. Online learning has been a valuable resource for some children but inaccessible to many others. In the medium term it is imperative that governments ensure access and infrastructure for technology (in particular internet access) and secondly that schools’ chosen education technologies conform to an appropriate ‘minimum online standard’ of good quality and protect children’s rights and privacy.

Countries should be wary of seeing education technology as a ‘silver bullet’. In fact, as Dr Björn Haßler of the Edtech Hub warns (16th April 2020), moving to online learning could ‘further disadvantage the poor’: ‘We are seeing massive proposals for aid aimed at pivoting to online learning. Firstly, this will not benefit the rural poor; secondly, it effectively drains funding away from the rural poor: there will be funding fatigue following the pandemic’. It is therefore vital that governments remain committed to reducing inequality and education budgets remain protected and equal to, or above, pre-crisis levels.

Long term solutions (three years +)

‘Though school closures may last months, their effects could last a lifetime’

Young people face a daunting future. Though school closures may last months, their effects could last a lifetime. As a result, policies need to take a long-term approach to tackling the educational inequality that has widened in COVID-19 in order to prevent it becoming economic and social inequality over a generation. As Andrabi, Daniel and Das point out in a comprehensive study of the effects of the 2005 Pakistan Earthquake (after which schools were closed for four months), four years after the earthquake those children who had fallen behind in the lockdown had lost a further 24 months of schooling. These children’s earnings would be 15-18% lower than they should have been for the rest of their lives. For a fairer future it is vital that we support those children now affected right through to their adulthood.

Young people should be at the centre of plans to ‘build back better’ from COVID-19 and reshape our economy toward a greener future. In the UK alone, the Resolution Foundation predicts that over a million young people under 25 will face unemployment and ‘years of reduced pay and limited job prospects’. At the same time the UK Committee on Climate Change are pressing the government to support ‘reskilling, retraining and research’ for a net-zero economy, and some politicians have called for a ‘zero-carbon army’ of new green jobs. Young people should be at the centre of these plans.

Finally, young people should be given greater power to shape the future they will inherit. 50% of the world’s population are under 30, yet only 2% of elected legislators are and the wealth gap between the young and the old will be further widened as young people bear the economic brunt of COVID-19. More young leaders, #nottooyoungtorun and political participation campaigns, youth budgets and lower voting ages would be valuable steps towards a future with young people at its heart.

Conclusion

This is what it feels like to live through history. Children are enduring the greatest educational disruption since the Second World War and young people are about to enter an economy in its worst state since the Great Depression. But catastrophe is not inevitable. The 1930’s led to fascism in Europe but Roosevelt’s New Deal in America. The pandemic has shown us the fragility of our world but also its strength and the risks and extraordinary sacrifices ordinary people are willing to endure for their society. This should give us hope that we can forge a fairer, greener future with young people at its heart if we only have the courage to seize it.

AUTHOR

SAM WILSON LEADS THE WYESIDE EDUCATION WORK AT WYESIDE CONSULTING. SAM HAS AN MA IN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND POLICY FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS, SEVEN YEARS TEACHING EXPERIENCE ACROSS YORKSHIRE AND IS A FUTURE EDTECH FELLOW WITH THE ODI.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Wyeside Consulting Ltd.

This article is the fourth of five looking at education and COVID-19:

1. Education and COVID-19: the impact in England

2. Education and COVID-19: the impact on vulnerable children worldwide

3. Education and COVID-19: the response in England

4. Education and COVID-19: ideas for a fairer, greener, more youth-centred future

5. Education and COVID-19: voices from the frontline

Subscribe to stay up to date with future blogs here

Follow Wyeside Consulting on Linkedin to stay up to date with all articles.