On 30 January 2025 the Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights handed down a judgement in the case of Cannavacciuolo and Others v Italy.

The Court held, unanimously, that the Italian state’s prolonged inaction to address illegal waste dumping, burying and burning in the area north of Naples that has come to be know as the ‘Terra dei Fuochi’ or ‘Land of Fires’ was so comprehensive as to breach Article 2 (right to life) of the European Convention on Human Rights. This is the first such ruling by the court, and it has been fairly described by campaigners as ‘seismic’.

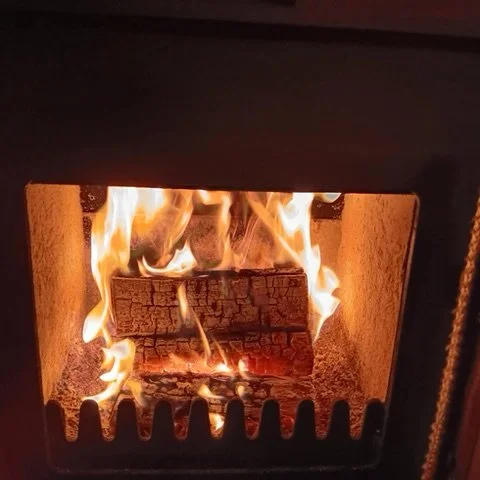

Organised criminal groups, such as the Camorra, have been dumping, burying or burning municipal and hazardous waste across a wide area covering 90 municipalities with a population of 2.9 million – 52% of the population of Campania - turning it into what has become know as the dustbin of Italy, ‘la pattumiera d’Italia’.

The Court found that the Italian state had failed to deal with a serious situation in the comprehensive way that it required, despite numerous investigations and reports, including no fewer that seven parliamentary commissions of inquiry. Specifically, the state had failed to assess the problem comprehensively, to prevent it from continuing and to communicate to the public affected.

The Court also held unanimously under Article 46 (binding force and enforcement of judgements) that the facts justified the exceptional procedure whereby Italy was required to draw up a comprehensive strategy to address the situation, set up an independent monitoring mechanism, and establish a public information platform.

The judgement in the case is really remarkable, and reflects the long, hard road taken by the applicants, 41 Italian nationals, most of them personally deeply affected by the health impacts of the waste in the Terra dei Fuochi and suffering from various forms of cancer. Applications were lodged with the Court on dates between 2014 and 2015.

The catastrophic waste practices complained of include digging pits almost down to the aquifer, dumping unsorted municipal and hazardous waste in them and covering it over; dumping waste in streams and rivers; burning waste along roadsides; burning banks of tyres; mixing wastes with compost and ensuring deep contamination of all the land on which it was spread. The scale of the problem is enormous: one report spoke of 55,000 tonnes of waste along public roads, 110-120,000 tonnes waiting for treatment. Between 2012 and 2018, 14,457 fires were registered in Naples and Caserta municipalities.

The environmental damage has been comprehensive, and the human health effects dire. There is dioxin contamination across a wide area, with ‘persistent poisoning of the soil’. Hightened rates of cancer have been noted throughout the area in numerous reports with titles like ‘Inquinamento ambientale ed effetti sull’incidenza dei tumori, delle malformazioni feto-natali, ed epigenetica’. Air quality, soil health, contaminated aquifers and waterways, spoiled agricultural produce, such as restrictions on buffalo mozzarella produced from animals grazing on heavily contaminated land, child birth defects and child cancers, this area has seen it all. The US Navy conducted its own studies into the health implications locally, and recommended its personnel to live on or above the first floor of buildings and to drink only bottled water.

It is not that the Italian state has done nothing, rather that it has not done enough. There were Parliamentary commissions of inquiry in 1995, 1997, 2004, 2007, 2013 (declaring an ”environmental disaster”), 2018.

Italy faced challenges by the European Commission for breaches of the Waste Framework Directive in 2005 and a judgement from the Court of Justice of the European Union ‘CJEU’ in 2007 (Case C-135/05) where it did not dispute the presence of 700 illegal tips containing hazardous waste. The Commission brought a new case in 2000 (Case C-297/08) resulting in another CJEU judgement in 2010 noting a “structural deficit” in installations needed for waste. A third Commission challenge was brought in 2013 (C-653/13) resulting in a third CJEU judgement in 2015 and fines. There were court cases, Parliamentary commissions, agreements across regional governments and 80 municipalities, reports, but implementation and action always fell short and practical remedies were missing. As the Court judgement noted (para 299) -

“The applicants complained about their exposure to an ongoing situation of diffuse pollution and the State’s long-standing failure to take action not only to prevent this pollution but also to mitigate its consequences, such as decontamination. They emphasised, in this connection, that the authorities had not adequately protected their lives and health. They pointed out that they had all contracted cancer.”

The Court also held that ‘given that the general risk had been known for a long time […] the fact that there was no scientific certainty about the precise effects the pollution may have had on the health of a particular applicant cannot negate the existence of a protective duty’ (para. 391). This is important , as the absence of certainty has been a barrier to other claims.

It is difficult to say whether even this hugely significant ruling could ever be sufficient to address the grievous harm done, to these applicants and the 4,700 other applicants whose 36 related applications have been adjourned, and to the people of the Terra dei Fuochi, by vicious criminality and state inaction.

In terms of the law, the Court denied legal standing to various outside groups that sought to intervene in the litigation on the grounds that they did not live in the affected areas. But it seems that it heard, and took careful note, of legal representations made by ClientEarth, Macro Crimes, the Forum for Human Rights and Social Justice of Newcastle University, Newcastle Environmental Regulation Group of Newcastle University, Lets Do It!Italy, Legambiente and other distinguished professors.

Between them, these applicants and their supporters have moved the dial, and the case is now a resounding precedent that will be heard across all signatory parties to the European Convention of Human Rights and beyond. The failure of states to address environmental pollution as serious as this with matching seriousness and urgency can constitute a failure in law by the states to deliver that most basic of all rights, the right to life.