In the late 1990s, while undertaking a Harkness Fellowship in the USA and working on a book on ‘Making Environmental Laws Work’, I visited Silicon Valley to talk to some of the company managers there about environmental regulation and the US computer industry.

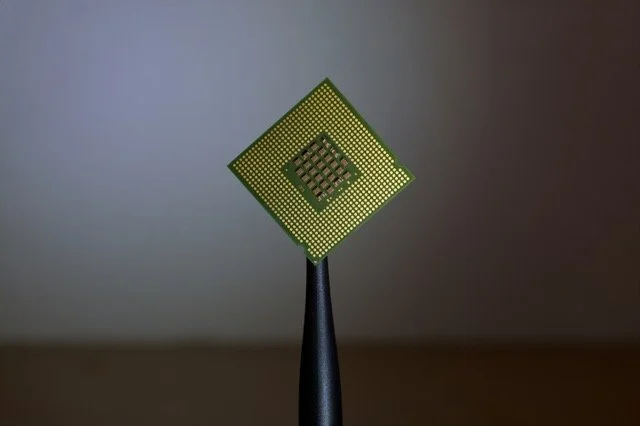

The investment on the structure and content of new chip fabrication plants was huge then, and will be far more now. One company where I conducted interviews was building a new semiconductor plant in Washington state. It planned to spend $500 million on buildings, and $800 million on equipment that it expected to have to replace completely within 5 years. It aimed to spend whatever it had to spend on pollution abatement equipment, in order to get into production quickly, and to stay in production continuously. Every day’s lost production was seen then as costing a fabrication plant between $1 million and £2 million, per day.

Anything, therefore that held up the issue of environmental permits became a major issue. As the Environmental Health & Safety Manager for one of the major companies, and Chair of the Environmental Committee of the Silicon Valley Manufacturing Group, told me, “three months can kill you”. The company’s products had a technological shelf life of only eight months.

The response of the Californian City of Fremont to this scenario, where the company was planning a new manufacturing plant, was instructive. As I wrote at the time -

“The city streamlined the permitting process, appointing one contact to co- ordinate all the permissions necessary, and within one week convened a meeting of all the utilities and agencies involved, so that the company could ensure that it met all their requirements at one time.”

The City of Fremont welcomed the proposed infrastructure development, it wanted the jobs, it wanted the taxes, and it took steps to understand what the applicant company most needed, and to make it welcome.

The City was not asking any individual regulator to remove or water down their regulatory requirements, or browbeating them to ‘go easy’ on their statutory responsibilities. It was simply ensuring that they all co-ordinate their requirements with a view to enabling the applicant to understand and meet them, efficiently and at the same time.

It is interesting to see evidence of a similar approach working well for the handling of state permits for major infrastructure developments in other parts of the USA today.